What do you keep stitched beside your heart?

Lincoln's greatcoat, American wound care, and a blessing for the menders.

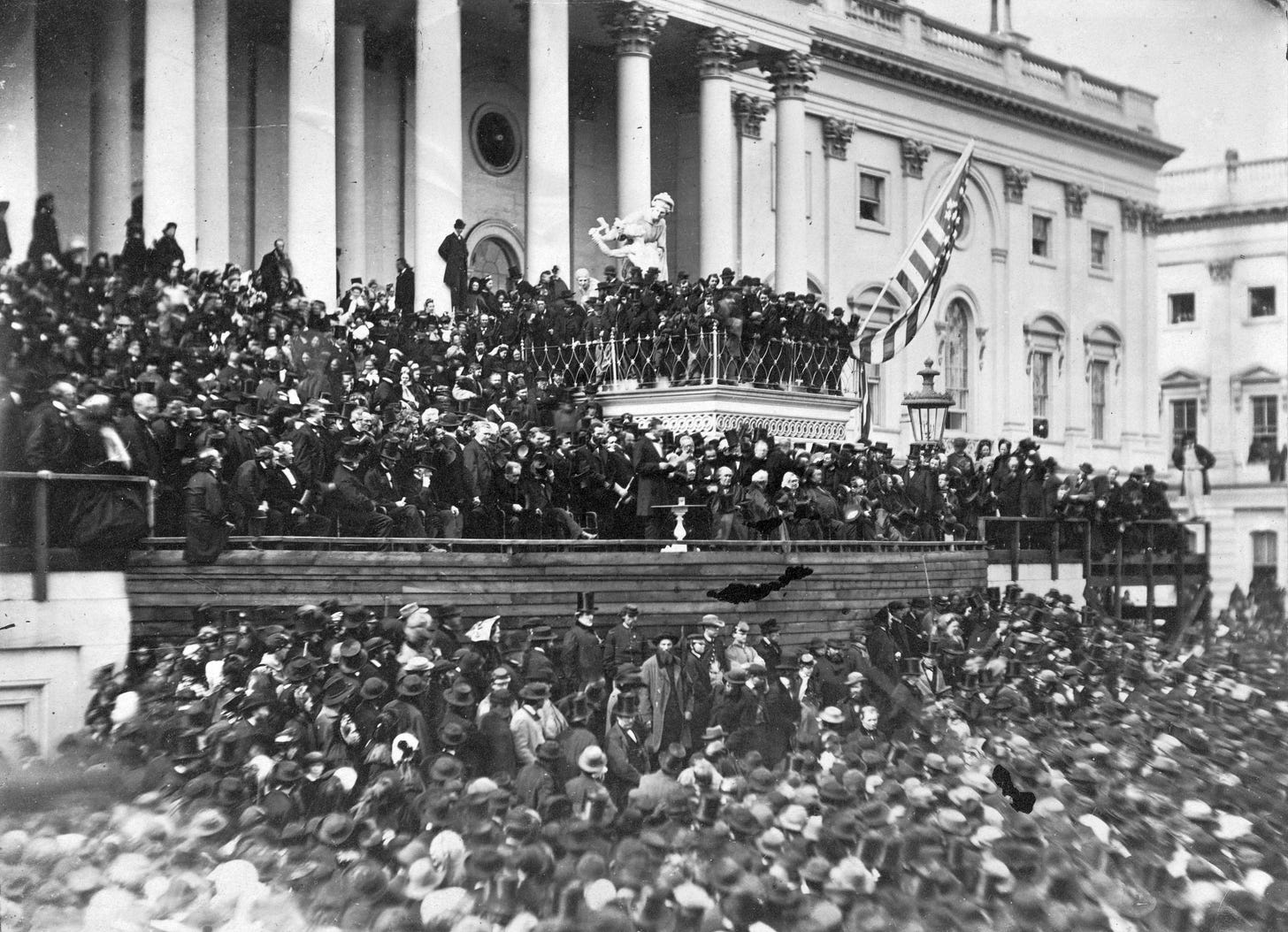

The morning of March 4th, 1865 broke with rains so fierce that the DC paper The Evening Star joked that “the police were careful to confine all to the sidewalks who could not swim.” Despite inclement weather, the east front stairs of the US Capitol building were crammed elbow to elbow, a small city of damp wool punctuated by stovepipe hats. Beneath the newly completed cast iron dome that has become an icon of American architecture, the crowd awaited Lincoln’s second inaugural address.

When Lincoln took the dais in his long, black greatcoat the clouds parted and the sun shone for the duration of his brief, 703-word speech. Lincoln was an imperfect man who made some decisions of questionable merit in an impossible situation; but that day, he wore the country’s sorrow on his craggy face and, in the span of under seven minutes, he named slavery a sin whose retribution from God the whole country had to face together.

He implored that Americans “with malice toward none, with charity for all” should strive to “bind up the nation’s wound,” and “do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Thirty-six days later, Lee surrendered his troops at Appomattox Court House. Six days after that, Lincoln was dead.

The address is well-known, second only to the Gettysburg address in textbook prevalence. But it’s a lesser-known detail of this historical day that I keep coming back to. Lincoln’s greatcoat had been custom made for his tall, slim frame by Brooks Brothers when the company was still run by eponymous brothers Elisha, Daniel, Edward, and John. This was not unusual – almost all American presidents have been outfitted by Brooks Brothers since the Madison administration. It’s what was inside the coat that set it apart.

Lincoln kept a treasured sentiment secreted beneath the coat’s long, wool panels. Hand-embroidered with black thread on the black, silk lining, an eagle with wings outstretched held a banner in his beak. It read “One Country, One Destiny,” a phrase borrowed from a speech made by Lincoln’s role model Daniel Webster some thirty years earlier.

Lincoln wore the tenet most important to him quite literally beside his beating heart: a promise made in silk thread and kept warm by the heat of his body. He was wearing the coat with its quiet, hidden promise when he was shot; in the subsequent years, swatches from the coat’s lining stiffened by the president’s dried blood were given as relics.

I spend a lot of time wondering if it’s possible to “bind up the nation’s wound” like Lincoln urged or if we’re witnessing the abscesses from too many hasty attempts to close the injury without addressing its depth. In medicine, the word “intention” has an additional meaning:

“There are three general techniques of wound treatment; primary intention, in which all tissues, including the skin, are closed with suture material after completion of the operation; secondary intention, in which the wound is left open and closes naturally; and third intention, in which the wound is left open for a number of days and then closed if it is found to be clean. The third technique is used in badly contaminated wounds to allow drainage and thus avoid the entrapment of microorganisms. Military surgeons use this technique on wounds contaminated by shell fragments, pieces of clothing, and dirt.” – Britannica entry on Surgery

Correct intention is crucial. America’s wound is a deep one with enough shell fragments to smelt into a skyscraper and enough scraps of clothing to stretch a quilt from sea to shining sea. A dear friend who is, among many things, a street medic, foot care practitioner, and a wilderness first responder once explained to me that wound healing is a long game; it requires dedicated attention and steady care. Intention, attention, the tension of a stitch, the tension of a historical moment: we’re asked to sit with the trauma, learn its ragged contours, know when and how to stitch and care for it. Blessed are the menders.

This is not fast work. If you have ever embroidered - or, for that matter, waited patiently as a bone or incision knit itself back together - you know the pace of the work is out of joint with the pace of our world. Between the speed of media and the ubiquity of capitalism, it can feel like we’re living in an endless commercial break. We’re rich in distraction, swimming in spectacle. Pro wrestlers are offering prognostications at political conventions. Panem et circenses.

I’ll put my jaded, heavy faith - my shambolic hope - in small stitches and the ones who make them. If you opened your figurative greatcoat, what sigil or saying would you harbor there? To what belief do you cleave in your secret heart? What world are you building unseen, slowly and methodically, stitch by stubborn, steadfast stitch?

I gotta go with Kierkegaard's 'Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.' Great job, as always!

Wonderful and prescient post! This outline applies so well to wounds literal, cultural, emotional, metaphysical, etc. The stitch is not the same as the healing. And scars can denote a beautiful lesson.