Forgive me, Substack, for I have sinned: during the time I should have carved out for writing this newsletter, I redid my guest room closet doors. With good reason, though. The 1970s-era sliding mirrored doors were a minor crime against humanity.

Everyone who stayed here would timidly ask, “is this mirror….correct?” and the answer was No. It was mean as hell. It made you look squatty and somehow knew everything you’d ever done wrong in your life. It belonged in some kind of Dantean hell ring dance studio. I listed it on the neighborhood Buy Nothing group. A kind woman named Danielle came and picked it up. I pray for her at night.

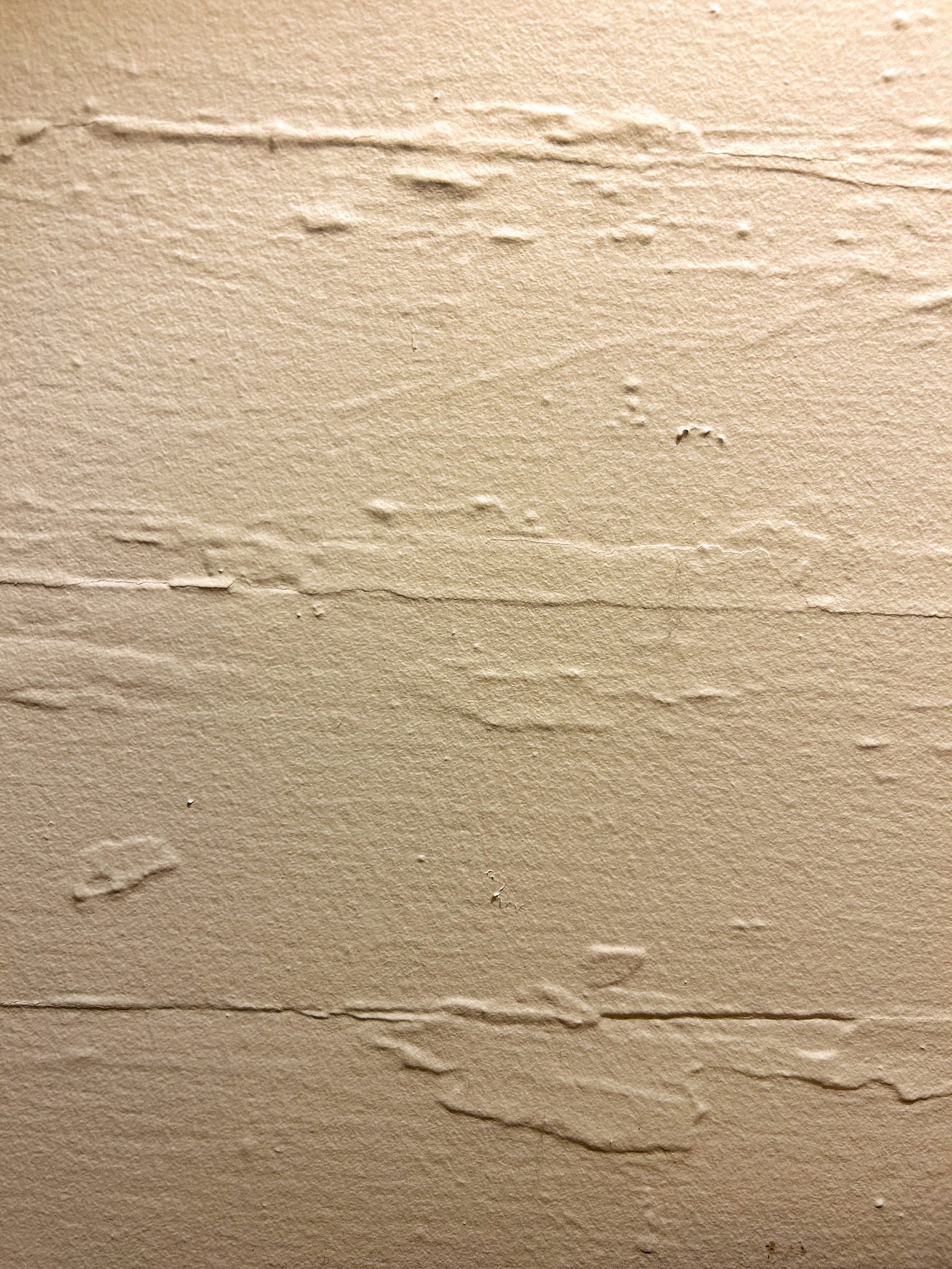

In the what-should-have-been-straightforward process of putting up some bifold doors, I was confronted with the immense crookedness of my sweet home. I find it endearing and charming except for when hanging pictures and doors. It brought to mind, though, a piece I wrote in the heart of the pandemic when time became an alien concept and I grew intimately aware of my home’s quirks.

So please accept this offering of a slightly older piece and a view of my newly upgraded closet doors. I clearly haven’t gotten over my gilding obsession just yet…

The Good Ship Dolores

There’s a spot in my 1930s mill house I call “Drunk Sailor Corner.” From its vantage, you can see into four different rooms without catching sight of a single right angle. The overall effect is something between the gauzy swim of drunkenness and the unwelcome dervish of vertigo.

It’s like being on a boat.

The three-inch heart pine planks that make up the floor, walls, and ceiling contribute to the nautical feel. Before shiplap was the gospel of every white-toothed television interior designer, it was a practicality: on a boat, it makes for a watertight hull. In old homes built before sheetrock, the boards sheathed the framing and hid the tangle of wires within the walls. By the time I moved in, Dolores’s planks had been repainted so many times, their surface rippled with tiny crags and valleys like a topographical globe.

The name wasn’t my idea. During the home inspection, as I waited anxiously for news that the place was haunted or had a family of nine raccoons living in the walls, I asked the house its name. Dolores popped into my mind, clear and insistent. I looked up the meaning on my phone: sadness and pain. Not an auspicious start for me and the ghosts and the raccoons. I also saw it listed as the 13th most popular girl’s name in the 1930s, the decade the house was built. That convinced me of a certain domestic sentience. Fine, I thought. Dolores. Dolly for short.

The inspector said the house was in surprisingly good shape for a bungalow pushing ninety. But, he mentioned casually, he had to report the asbestos siding as a formality. I asked him if I should be worried. He shrugged. “Don’t lick it,” he suggested. “Undisturbed, it’s fine. Just don’t mess with it. It’ll protect you from fire.”1

I hadn’t even hung pictures on Dolores’s walls when the pandemic struck. The world shrank to 900 square feet, and we lifted anchor. The crew consisted of one (1) writer in her 30s and one (1) small black cat. I learned quickly the essential tasks required to keep a vessel afloat. I trimmed the sails and made soup, planted bleeding heart and foamflower. In the beginning I counted the days, maybe a week or two, then stopped.

Time unspooled in lumpy intervals; the hours between lunch and dusk often dilated by several days while some weeks evaporated altogether. I sat down to read, but sentences refused to hold together. I put up a light fixture and found more asbestos insulating the wires the way myelin hugs a neuron. It was menacingly frayed. I tried to hang bookshelves, but the heart pine walls fought back. After each hole I drilled, I had to pry a sticky corkscrew of sawdust from the grooves of the bit. My fingertips smelled like sunbaked conifers, a little like lemons. The walls were so infused with resin that the holes began to ooze shut if I didn’t put a screw into them immediately.

This resin was the reason seafarers have had a long love affair with heart pine. Burned to a sticky pitch, it was used to waterproof boats from stem to stern: an inoculation against drowning born of fire. It made the tree’s tall, straight lumber rot-resistant; the herculean keel of “Old Ironsides,” the oldest ship still on the water, is carved from a single heart pine timber.

A kinship developed between me and Dolores. I gave her gutters, and she kept me dry through a tempestuous summer. I accommodated her electricity quirks – using the coffeemaker and toaster at the same time would flip the breaker, submerging the kitchen in darkness – and she stayed on the right side of the water the days when my mind crackled with too much static for use. They say that over time people begin to resemble their pets; I wondered if the same might be true about homes.

I had paced Dolores’s floors countless times before discovering they were legible. The boards, almost a century old themselves, were made from trees far older still. On some planks, the length of my lifetime could fit beneath the width of my thumb. Stories about drought and pestilence, lightning and fire were written in the wine-dark rings between summer growth. For all her wonky angles, Dolores has survival scrawled in her pine bones.

But nature demands tradeoffs. While the shipwright holds a torch for heart pine, heart pine is in love with fire. The trees rely on regular burn cycles to thrive. Called “fat wood” or sometimes “lighter knot,” the resinous wood is an unparalleled fire starter and catches at the slightest provocation, even when damp. It burns hot and bright. The pitch seethes and boils as if water were pouring from the wood.

On the flipside of Dolores’s durability is an itch for immolation. If fire ever comes to her, it won’t be from the outside. The asbestos siding will do the job asbestos has always done. Naval ships were shrouded in the stuff to safeguard the same sailors that later died from their exposure to the carcinogen. Sometimes the ways we protect ourselves turn out to be the most damaging things of all.

If fire visits Dolores, it’ll be an inside job. Some old vestiges of faulty wiring, of ancient knobs and tubes, will overheat and smolder in the hidden recesses of her hold. On nights when my own wiring runs hot and sleep eludes me, I convince myself I can smell the sweet resin catching in the crooked walls.

This is my quiet terror: not the sea or the solitude, but that a spark will quietly kindle, unnoticed; that the walls will stream with steaming pitch; that the whole thing will bloom into a dazzling conflagration on the water; that other ships will see the bright flower on the distant horizon and think “isn’t it beautiful?” as she burns and burns and burns.

A post-script: in case you are worried, I DID have the electric checked when I first moved in by a qualified professional, and it’s as safe as possible prior to a rewiring job, which I’ll do…eventually? Similarly, my psychological wiring is also stalwartly adequate most days. Another way Dolores and I mirror one another as we make our winding way through the world.

Fun fact: did you know that the Romans used to weave table linens out of an asbestos blend and just THROW THEM INTO THE FIRE to clean them at the end of a meal? They did notice that the weavers had a tendency toward pulmonary issues, though…

Daggum, K, you make me laugh out loud, every time. Funny on!

I feel like the post-script was specifically for me.