The stubborn insistence of the human brain is a fascinating thing. We know, fear, and hold charity races for the many ways the mind can fumble, deteriorate, and succumb to entropy. But we nurse a fascination for the ways it persists in the face of assault and deprivation.

Take for instance the macabre Psychology 101 textbook tale of Phineas Gage, a railroad construction foreman whose life was somehow only mildly disrupted by an explosion that javelined an iron rod through his cheek, eye, and left frontal lobe before exiting through the top of his skull and landing 25 yards away.

While his family noted that his personality changed after his incidental lobotomy, it turns out those aforementioned psych textbooks that made post-incident Gage out to be a brawling drunkard may have taken a bit of poetic license. Recent research suggests that what we think we know about Gage might be highly embellished at best and a fabrication at worst. Far from transforming into some kind of Mr. Hyde, Gage developed a deep fondness for animals and children after the accident and placed significantly less emphasis on the value of time and money. Sounds like my kinda guy, TBH.

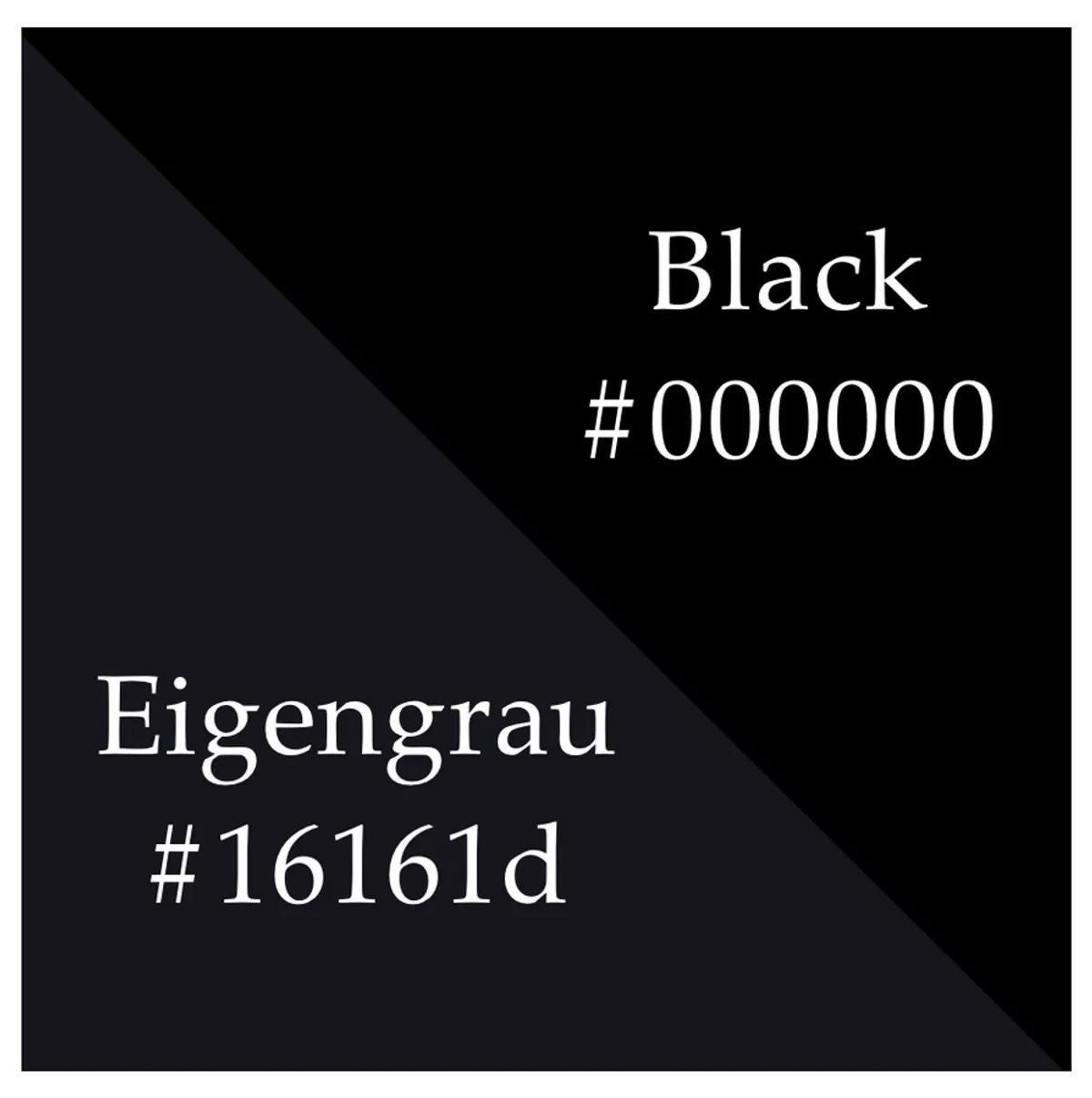

Or consider the weird, dark glow of Eigengrau, or “intrinsic gray” also called “brain gray”: the luminescent dark gray the brain creates in the complete absence of light in an effort to provide contrast. It’s the not-actually-black you see with eyes closed in a darkened room. It arises when rhodopsin, a photo-receptive protein in the eye used in twilight vision and responsible for turning light information into electrical information, spontaneously triggers in the absence of a light stimulus. A grim, extreme version of this phenomenon is known as “prisoner’s cinema”: a light show of various colors and forms reported by prisoners held in prolonged periods of darkness.

Another intriguing testament to the brain’s tenacity is phantom limb pain in the wake of an amputation. Cursory consideration leaves most of us with a rudimentary, and inaccurate, belief that one cannot experience pain in a limb that no longer exists. What isn’t there can’t possibly hurt, right?

Wrong. So very wrong. Phantom limb pain can be a debilitating, chronic condition for up to 80% of people following limb loss. The condition remains poorly understood, but the general explanation is that though the limb is gone, the part of the brain that it mapped to remains active; the mind can’t initially comprehend that a part for which it has always been responsible – that it coordinated for walking or writing, that it ensured never got dangerously hot or cold, through which it understood the dampness of dew — is no longer there. It still sends nerve signals as if it were. And sometimes those signals shriek. These neural responses can manifest as stabbing knives or searing coals or the endless infuriation of an unscratchable itch.

Phantom pain is a corporeal grief, a stark absence that the brain can’t quite remember to remember. It’s like the gut freefall of reaching for your phone on instinct to call someone you’ve lost and realizing, again, they will never answer. It’s a ghost that haunts the body.

One of the most impactful therapies for phantom pain ingeniously outsmarts the brain at its own game. Mirror therapy employs a simple yet effective technique: positioning a mirror to reflect the intact limb and then freely touching and moving it. This sensory input convinces the brain that the absent limb can function without pain. While not universally effective (and not always feasible in people with multiple amputations), it has offered notable relief for many amputees for the comparatively low price of a flimsy closet mirror from Target.

There are other ways the brain confuses where the body ends and the rest of the world begins. When we witness the pain of another, some of the neural circuitry for our own pain lights up as if we were experiencing it ourselves. This shared neuronal network has evolutionary benefits for learning to avoid threats and promoting altruistic behavior. It’s the basis of empathy.

I’m a big fan of empathy. I fly the flag, quite literally, and think it’s a central tenet to my concept of humanity. But there is, it turns out, a hidden dark side to empathy that can calcify into inaction — or even violence. A paradigm-shifting 2014 study, called simply “Empathy and Compassion,” delineates the distinction between these two pathways empathy can follow:

“While empathy refers to our general capacity to resonate with others’ emotional states irrespective of their valence — positive or negative — empathic distress refers to a strong aversive and self-oriented response to the suffering of others, accompanied by the desire to withdraw from a situation in order to protect oneself from excessive negative feelings. Compassion, on the other hand, is conceived as a feeling of concern for another person’s suffering which is accompanied by the motivation to help.”

Empathic distress can be manipulated to further drive the wedge between a worthy “us” and a blighted “them”. Faced with this discomfort and stress, people regularly numb out or even lash out at the people who are suffering for “causing” their anxiety.

We all experience some cocktail of these responses; they are not binary. I have, more times than I’d care to admit, fumbled with the radio as an unhoused person walked by my car when I knew I had no cash on hand. I waited impatiently for the light to turn green, as if I could drive away from the systemic inequities that leave one person hungry and one comfortably listening to Led Zeppelin with a full belly on the way to her house. As if avoiding eye contact could keep my heart from twisting in on itself.

These pathways are also malleable; the study revealed that through focused meditation, people can strengthen their compassion response to another’s pain. Instead of the nail-biting discomfort of empathic distress, a compassionate response elicits feelings of connection and love and motivates action. And though the study focused primarily on loving kindness meditation, I know of other shortcuts to compassion.

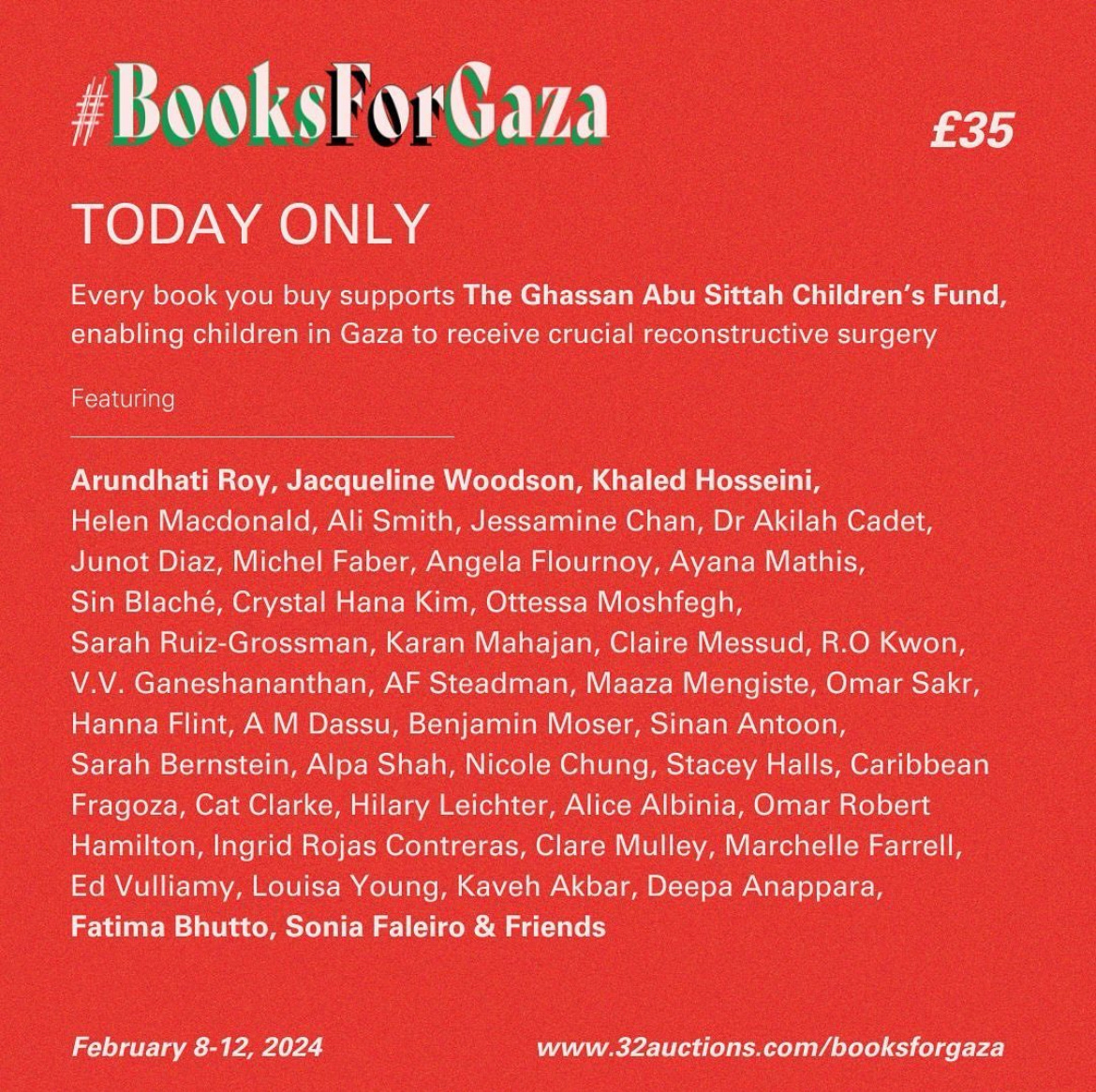

Today is the last day of the #BooksForGaza auction, a global coalition of authors who have donated their signed works to raise funds for injured Palestinian children. I bought a signed copy of

’s 50 Poems to Open Your World, edited by .The best poetry shunts you directly into a space of compassion. It is an incantation, a fairy tale spell, that lifts you out of time and space to place you — for the space of a few lines — alongside the poet, to see what they see and feel what they feel. Poetry does just what this collection suggests; it “opens your world” to the vast panoply of human experience, as radiant and excruciating as that is.

Every day in Gaza, over 10 children lose one or more limbs. Under normal circumstances, many of these limbs could have been saved. But under the constant threat of bombing and a debilitated healthcare system, the choice often becomes a limb or a life. Sometimes that choice is made without electricity. Sometimes without anesthesia.

To be haunted by the phantom of pain is horror enough. The phantoms that will stalk these children — of family, of home, of stolen youth — are almost incomprehensible.

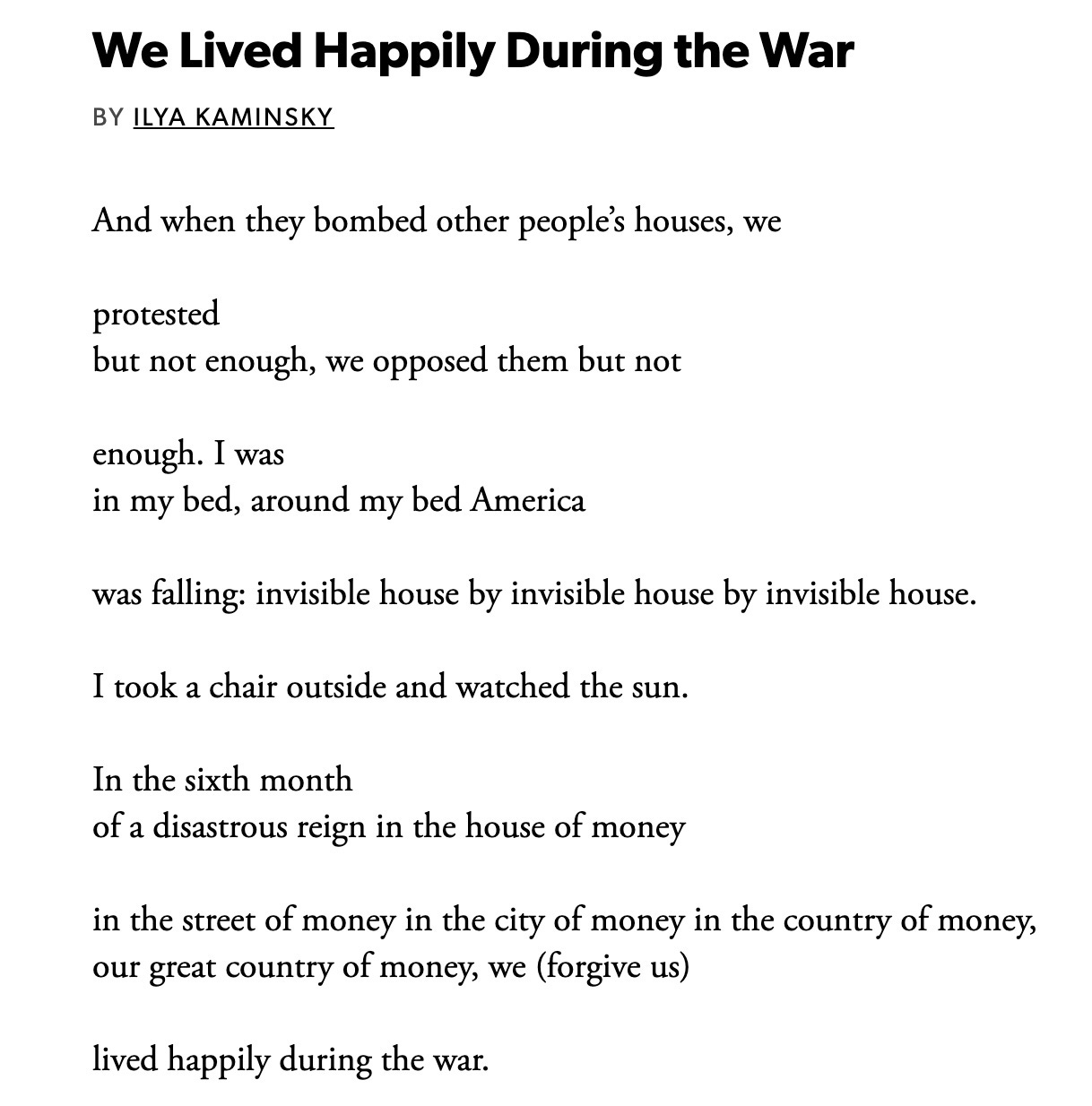

As the Super Bowl game stretched into overtime, Israel carpet bombed Rafah, a city of 300,000 people now filled to bursting with 1.5 million civilian refugees with no place to go. I thought of an Ilya Kaminsky poem in my newly purchased collection:

I have watched people toggle off their compassion for a season now — a kind of spiritual severing in an effort at preservation. On some days, I have been one of them. Autotomy: the way some lizards drop their tails if they feel endangered by a predator. I can’t help but wonder what phantoms will haunt us for turning away, what mirror could be wide enough to heal us.

“Depths of Despair” is Pantone color of 2024

Deep and beautiful, as always. On the more trivial end of the spectrum, due to partially detached retinas (my missing limbs?), I have blind-spot areas, and so Eigengrau is a (very) close friend of mine, in fact a constant companion. On the far other end of the spectrum are the Grotesqueries of Gaza; the depravities of the original attack were many, the depravities of the response are infinite. And the irony of forcing perceived 'non-humans' into the concentration camp that is now Rafah and thenuse of white phosphorous on humans is overwhelming. Maybe these victims are not phantom limbs but phantom humans whose painful absence will be felt as long as empathy lasts.