When this arrives in your inbox, it will be exactly one hundred and eleven years since the Titanic struck an iceberg and reached out in its distress. Two ships could have come to the doomed vessel’s aid. One did.

Our world is perched on a continuum of care. On one side are the enlightened saints and the wildly codependent who put the wellness of others above all else. On the other are the “greed is good” kind of folks who wouldn’t bat an eyelash at scamming the old or conning the vulnerable.

Once, I would have put “decent” right in the middle, a sort of morally neutral fulcrum. But thanks to peak capitalism and its resultant resource hoarding and rabid obsession with maintaining power at all costs, the center has moved. The bar has been precipitously lowered.

Now, I feel like plain old “decent” is a minor badge of honor; it certainly feels like the most you can reasonably expect out of anyone. In the title track of his posthumous album Thanks for the Dance, Leonard Cohen gently concedes that “there’s nothing to do/but to wonder if you/are as hopeless as me/and as decent.”

I think that’s the question I’m silently wondering of everyone I meet these days. Though I’m not in line for any humanitarian awards, I certainly strive for at least the bare bones of decency. But there’s a little phrase I mumble to myself when I want to do a bit better than merely decent:

“Be like the Carpathia.”

The name probably sounds familiar – it’s the ship that on this date 111 years ago saved the survivors of the Titanic disaster. But the story’s details are what make me repeat the ship’s name like a mantra.

You know how it begins: 11:40PM, lookouts on the RMS Titanic felt their stomachs drop in panic as a silent behemoth emerged from the fog directly ahead of them; even an “unsinkable” ship is no match for a tower of ice. They rang bells, alerted the bridge, reversed the engines, and breathed a sigh of relief as the ship slowly grazed alongside the frozen giant.

Snow rasped from the berg glittered down on the forward deck. Passengers made snowballs out of it and laughed as they threw them at one another. They didn’t know, yet, that a jagged talon of ice had torn a 300-foot gash in the ship’s starboard hull.

An hour prior, the SS Californian had sent a message to nearby ships warning them of ice. A decent thing to do. The harried wireless operator of the Titanic was slogging through a backlog of transmissions from the ship’s wealthy passengers and didn’t report the message to the bridge. Moments before the Titanic began taking on water, the sole Californian operator switched off the wireless and went to sleep.

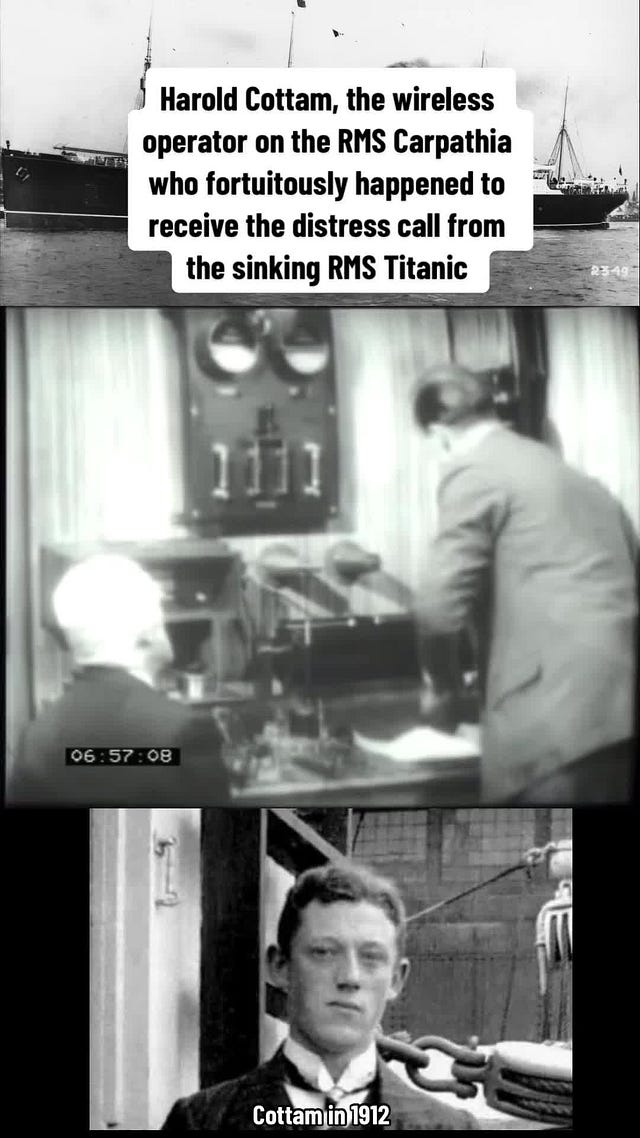

By all accounts, the next nearest ship at 58 miles away, the Carpathia, should have missed the Titanic’s distress signal. The wireless operator, Harold Cottam, was on the bridge reporting the day’s events when the call was first transmitted.

But ol’ Harold was a nice guy. Even though his shift was over, he left the transmitter on as he unlaced his boots before bed. He heard a transmission that a backlog of private traffic meant for the Titanic wasn’t getting through.

Now here’s one of those moments where one tiny gesture radically altered history, the kind that could spring upon you on any given Tuesday: Cottam decided to help out when he could have gone to sleep.

He took the messages meant for the doomed liner, and when he tried to relay them, he received the urgent response: "Come at once. We have struck a berg. It's a CQD, old man." CQD predated SOS as a general call conveying distress.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Cottam woke Captain Rostron who immediately comprehended the gravity of the situation. He wasn’t even fully dressed when he commanded the ship be turned around and outfitted to save whatever souls it could.

Formal dining rooms were transformed into first aid stations. Coffee, soup, and tea were prepared in enormous quantities. Passengers readied clothes and blankets.

Here’s the thing about the Carpathia – she wasn’t a high-end luxury liner. She was cozy and comfortable, stable and slow. Where the Titanic’s top speed was 23 knots, the Carpathia’s was a pokey 14. That meant it would take the ship 4 hours to arrive at the Titanic’s aid.

The top speed of a steamship was more of a warning than a suggestion. Propelling the sheer mass of those ships through the water with the elemental forces of coal, fire, steam and pressure was a dangerous affair. There wasn’t much wiggle room to safely pick up speed. Not even a knot.

In the middle of the frigid Pacific in the wee hours of the morning, Rostron cut the hot water and central heating from his ship to divert all steam power to the engines. Not a single passenger complained.

A crew member put his hat over the gauge that showed how hot they were driving the ship, how in the red they were running. They already knew. The Carpathia was traveling at 17 knots.

And what was the decent Californian doing as terror and tides ripped through the Titanic? Though it was not responsive over wireless, the Californian was close enough that its lights could be seen from deck of the sinking ship. The Titanic attempted communication by Morse lamp and then with eight flares, illuminating the sky with her desperation.

The Californian noticed these signs of panic but wrote them off, like so many of us do, as *probably nothing to worry about*. Reports say they noticed the ship seemed to be acting odd, as if part of it were canted out of the water. By the time they tried Morse lamps, the Titanic was unresponsive. When the lights on the Titanic finally winked out around 2:00 AM, the crew aboard the Californian assumed they had sailed away. They never woke the wireless operator.

The next flares seen as the April sky edged toward sunrise were from the Carpathia to let any survivors know they were coming. They had shaved a half hour off of their ETA; it’s impossible to know how many lives those thirty minutes saved. But of those who had made it into the life boats, only three died by the time the Carpathia arrived.

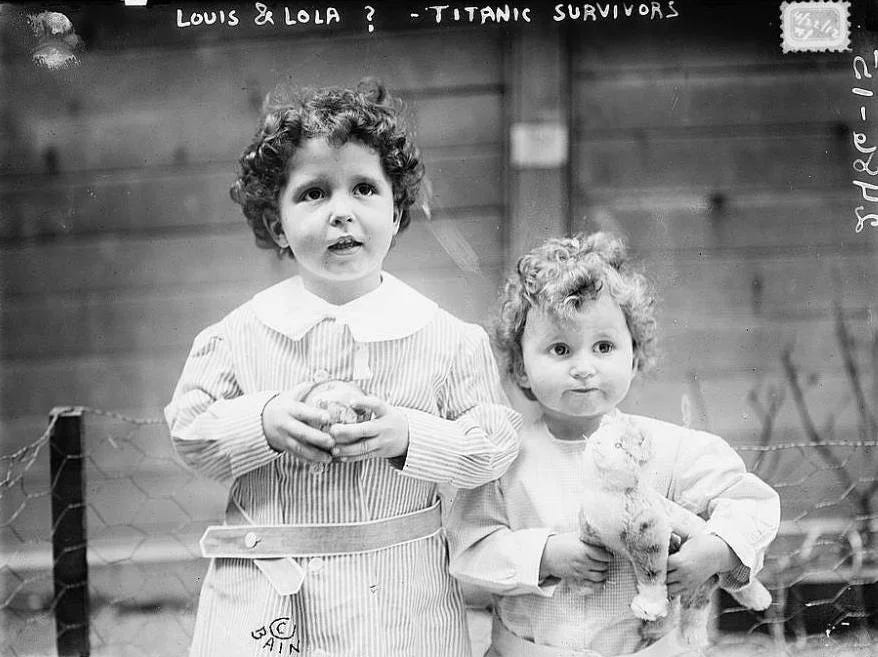

The Titanic’s manifest had 2,208 names on it; 705 of them were lifted into the warmth of the Carpathia. Waiting arms wrapped men, women, and children shivering with cold and shock in blankets and sat beside them, held them in their raw grief.

History would have forgiven the Carpathia for saying the distance was too great, the route too treacherous, the cause lost. The question becomes: what can we forgive ourselves? Without Cottam’s small act of kindness, without Rostron’s dogged determination, the sea might have swallowed every soul who sailed on the Titanic.

These days, there are so many people, creatures, ecosystems, moving strangely on the horizon, taking on water, broadcasting their distress in the only ways they know how.

It’s all too easy to switch off the wireless; to shove down that gnawing suspicion that something is wrong; to tell yourself that flares are fireworks.

(Yes, I know the deep importance of boundaries and putting on your own life vest first, etc. I follow plenty Instagram accounts reminding me about the merits of self care. And for day-to-day living, it’s healthy and important.)

But disasters come to us all eventually. And on the many blessed days when I’m not the one tossed by an unforgiving sea, I get to make a decision. Will I do the bare minimum to meet the bar of decency like the Californian? Or will I push myself to the edge of my own limits in heedless love like the Carpathia?

A beautiful, moving piece of writing. Thank you. And now I’ll always remember the Carpathia too.

Kimberly- This is such an important piece on the responsibility of being at sea with fellow humans. An important reminder.