An Unlikely Awe

Yet another Substack about the weirdness of a total eclipse - but not in the way you might think.

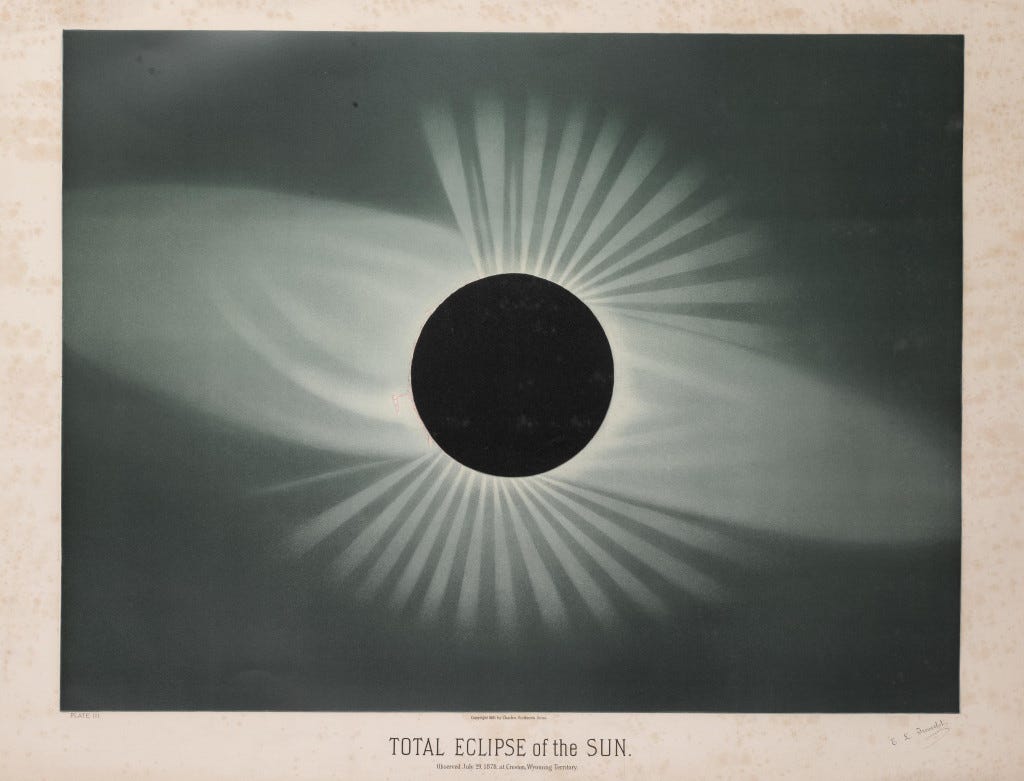

In 2017, I stood barefoot on the stubble of a freshly mown field in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains on a blazing August day. Then the world went dark. Crickets chirruped and coyotes whimpered and whooped half-heartedly, unconvinced of the sudden night in the middle of the day. Planets burned one behind the other like a strange game of astral billiards. A sudden dew dampened my feet. Light pooled in beads in the rifts and valleys of the moon’s surface just before daylight returned and the aubade of birdsong replaced the brief night music. I looked at the people around me, alien and intimate: some in tears, some grinning wildly, each grappling with their private understanding of the cosmic event we had just shared.

I do not possess the linguistic capacity to convey the ways an eclipse can bend one’s concept of existence, and even if I did, the patron saint of lyric nature writers beat me to it. Dillard’s essay opens with “It had been like dying” if that gives you any indication of the degree of intensity we’re talking about here.

In a recent episode of my favorite podcast, Ologies, NASA heliophysicist Dr. Michael Kirk affirms the soul-shuddering impact these eclipses have on people: “In terms of awe factors, people rank it just below seeing their child being born. It’s that level of deeply amazing…Personally, I would say it is the most amazing, awe-inspiring natural event you could witness.”

We have a conflicted relationship with awe in modern America; we love a spectacle but hate feeling insignificant. Our ambivalence is evident in our vocabulary; many etymology nerds (she says, gesturing wildly at herself) lament the demotion of the word “awesome” from describing things like a flood of religious ecstasy or the heart stopping view from the rim of the Grand Canyon to a particularly tasty turkey sandwich or a three paycheck month. Similarly, “awful” mutated from meaning full of reverence or fear to a sort of generic sense of very bad or an excessive amount.

Perhaps the terms have been slippery because our understanding of awe is in flux. At awe’s roots are a shuddering terror and the reverence commanded by something that could elicit such a response. Over time, its use in religious texts gave it a benevolent shine, more of a connotation with wonder. In his book Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life, Dacher Keltner defines awe as “the emotion we experience when we encounter vast mysteries that we don't understand.” Whatever it is, I treasure the bracing perspective it offers.

I cannot think of a shared event that so perfectly illuminates the tension of awe as a total eclipse: all of us fierce, fragile creatures poised perfectly beneath the moon’s shadow, suspended between the vertiginous terror of our smallness and the stunning grace of being a part of something so vast.

I won’t be in the path of totality today with millions of Americans; I’ll content myself with watching crescent shadows shimmy in the light cast between the leaves. But I have, as I’m wont to do, learned a single fact that I’ve been toting around like a talisman. It’s the kind of fact that lets me carry the soul-shearing power of an eclipse in my hands long after picnics and short flights and exorbitantly priced foil glasses have faded from memory. To be more precise, I carry it in my fingernails.

It's a fact that fills me with the same potent mix of worry and wonder that I felt seven years ago as the cold dew dampened my toes in the middle of a searing summer afternoon:

None of it should be this way.

I grew up thinking total eclipses were a cosmic inevitability like supernovae or comets. Turns out, the blazing ring of fire I had the good fortune to witness is a complete statistical anomaly. In rough math, the Sun is about 400 times the size of the Moon, which just so happens to be 400 times closer to us. It is by pure chance that these heavenly orbs take up the same amount of space in the sky – about a half a degree – when seen from Earth’s surface. No other planet in our solar system experiences perfect eclipses of their mostly-far-too-small moons.

Add to this the independently canted, elliptical orbits of the Earth around the Sun and the Moon around the Earth, and the odds of a total eclipse (instead of a partial or annular eclipse) shrink again. Only 40% of solar eclipses are total, and most of those occur over the ocean due to the simple fact that the seas cover 70% of the Earth’s surface. Tremendous luck or significant resources are required to be within traveling distance of a total eclipse in one’s lifetime.

But here’s the part that bends my mind to the point of breaking: we showed up to the party at just the right time. This unbelievable happenstance is finite in terms of astrological time – and we just so happen to be alive and sentient with the stubborn evolution of eyes to witness it.

When our Moon first formed, it was much closer to a faster-spinning Earth. Scientists speculate that our first days 4.5 billion years ago were about 6.5 hours long. Over the eons, the friction between the sea floor and the tidal pull of the Moon (if you’ve never seen this visualization of the tides, please enjoy the mindf*ck 🙃) have inexorably slowed the Earth’s spin. In a mathematical compensation that is above my pay-grade to understand called the conservation of angular momentum, the Moon has consistently moved away from the earth at a rate of 1.5ish inches per year.

Which also happens to be about the rate at which your fingernails grow.

All of that to say that many years ago, the closer new moon blotted out the sun entirely during the total eclipse, obscuring the majestic view of the flaming corona we see now. And 650 million years from now, the moon will have moved too far from Earth to obscure the sun entirely; all eclipses will be partial.

Or, in the words of well-starched Forbes magazine that read more like a foretold vision from a hag in a dark wood: “When the perigee full moon is smaller than the aphelion sun, no total solar eclipses will happen anymore.”

In my lifetime, a mere electrostatic spark in the wide spiral of spacetime, I have had the enormous privilege to watch the intricate choreography of the Moon and the Sun, to see the roiling mane of the Sun’s corona peeking through the mountains of the Moon. I live each day in the tug of their sweeping Viennese waltz swirling like the two electrons in a helium atom, freshly crashed into existence.

This is awe: perched between nothing and everything, looking at the translucent crescents of my fingernails keeping time with the Moon’s slow drift from the Earth. All of it chance, and we faced with the choice to call it happenstance or divine or center ourselves in the dizzying orbit of the two.

None of it should be this way. But it is. And we’re here to see it.

Now go chase that shadow.

P.S. - because I cannot resist the urge to share one more wonder that tickles my fancy beyond reason: the length of a day at the formation of the moon was extrapolated from data found in Tidal Rhythmites - patterns left in soil by ancient tides, some as old as 620 million years. They look like laminated pastry or mud dauber nests turned on their side. A tidal record two thousand times as old as humanity just casually hanging out for all the world to see. Wall. To. Wall. Wonders here, people.

The perfect thing to read just before an eclipse happens.

Thank you for teaching me a new word: aubade - a word for young people in love! It's beautiful.

As for all the other words, they sort of merged into one another until they lost most of their meaning in a mess of profundity ... but then again, I'm easily confused.